The Best Fluffy Pancakes recipe you will fall in love with. Full of tips and tricks to help you make the best pancakes.

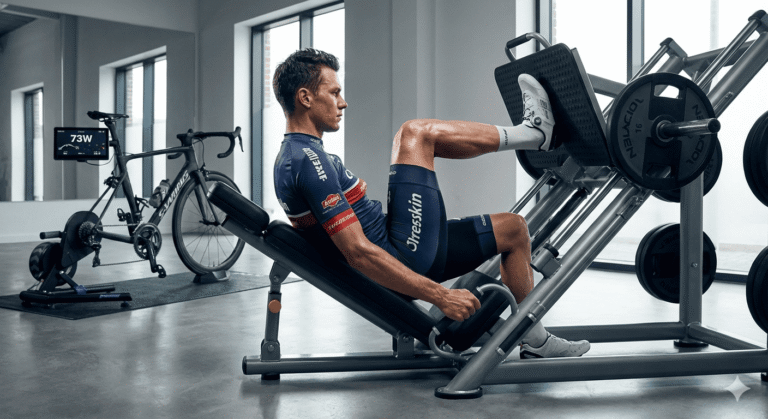

Flexibility & Mobility for Cyclists

Stretches and mobility flows to prevent tightness and improve comfort.

So there’s this thing about ships, bear with me here because I promise this connects to flexibilty for most cyclists. A ship leaves LA heading for Tokyo, right? And the captain adjusts course by literally just one degree. One. That’s nothing, you can’t even feel that kind of turn. But here’s where it gets weird: by the time that ship crosses the Pacific, it’s not pulling into Tokyo harbor at all. It’s 150 miles off, somewhere near Osaka maybe, or just… out there in the wrong place entirely.

One degree seemed like absolutely nothing when it happened. The crew probably didn’t even notice. But destinations? Destinations got completely rewritten.

And that’s exactly—exactly—what’s happening with your cycling and flexibility work right now, except you’re the ship and nobody told you about the degree shift. We get obsessed with the loud stuff (new carbon wheels, interval training that makes you want to die, shaving another 30 seconds off our FTP) while this quiet, almost boring practice of mobility work just sits there. Waiting. Being ignored.

But I’m telling you—and I’ve seen this with my own body after ignoring it for years—the tiny recalibration of consistent flexibility practice doesn’t just tweak where you end up. It fundamentally changes how your body moves, how rides feel in your hips and lower back, and whether you can still enjoy cycling at 65 or if you’ll be that person who had to quit because everything just… seized up.

Shift One: Stop Holding Still and Start Moving (Seriously)

Here’s the first shift and it’s going to sound almost too simple: ditch the static stretching routine—you know, that thing where you grab your quad and hold it for 30 seconds like a flamingo—and replace it with dynamic mobility flows.

Most cyclists who stretch at all (and let’s be honest, that’s already a small percentage) default to what their high school PE teacher taught them. Hold the stretch. Count to thirty. Feel virtuous. Move on. It feels like you’re being disciplined, like you’re doing The Work™.

Except—and this is where it gets frustrating because nobody tells you this—static stretching before you ride actually makes you weaker. Like measurably weaker.

There was this massive meta-analysis back in 2012, published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports (great bedtime reading, truly), and they looked at 104 different studies. The finding? Static stretching before exercise drops your strength by about 5.5% and power by 2%. Now that might sound like whatever, small numbers, but think about it: if you’re putting out 250 watts on a climb—which, let’s be real, is already hurting—you just lost 12.5 watts. That’s the difference between hanging with your group and watching them vanish up the mountain while you’re grinding away wondering why your legs feel dead.

Dynamic mobility is different. Completely different paradigm. Leg swings, hip circles, walking lunges with a twist—these flowing movements wake up your nervous system, get synovial fluid moving in the joints, and basically remind your body “hey, we’re about to do this thing where we pedal in circles for several hours.”

I started doing this about two years ago (after a particularly humbling conversation with a physical therapist who watched me try to touch my toes and basically laughed), and the difference is… it’s hard to describe because it’s not dramatic? But my hips just work better now. They remember they can do things other than the cycling position.

The shift takes the same five minutes. Same time commitment. But one approach locks you into your riding posture like you’re fossilizing, and the other one keeps you, I don’t know… fluid. Human-shaped.

Shift Two: Mobility Isn’t Medicine, It’s Food

Okay second shift, and this one is more about when and why you’re doing this stuff in the first place.

Most of us—myself included for years—treat stretching like it’s remedial. Like physical therapy homework after you’ve already screwed something up. Your hip flexors are screaming? NOW you stretch. IT band feels like a guitar string about to snap? Time to foam roll. It’s reactive. It’s damage control.

The one-degree shift here is reconceptualizing mobility as movement nutrition. As essential as the actual food you eat, the carbs you consume before a long ride, the protein you choke down afterward even though you’re not hungry.

You wouldn’t do a century without fueling, right? So why would you accumulate weeks and months of cycling-specific positioning—hunched forward, hip flexors shortened, thoracic spine rounded—without making regular mobility deposits to offset that movement debt?

This means shorter sessions but way more frequent. when you wake up (before coffee, which is when you know it’s serious), midday and before bed, 5 minutes each. It’s not about these marathon stretching sessions where you set aside an hour and try to fix everything at once—though I’ve definitely tried that approach and mostly just ended up frustrated and still tight.

The science behind this is something called viscoelasticity, which is a deeply unsexy term for how your connective tissue behaves over time. Fascia—that’s the weblike stuff that wraps around every muscle—responds to consistent mechanical input by reorganizing how its collagen fibers arrange themselves. Give it gentle, regular tension and fascia becomes more pliable, more hydrated (yeah, apparently fascia hydration is a thing), and it glides over underlying structures instead of sticking to them.

Ignore it? Fascia densifies. Adheres. Creates that stiffness that makes you feel ancient every time you get off the bike.

There’s research in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies—and yes, that’s a real journal—showing fascial tissue responds way better to low-load, long-duration stretching done consistently rather than aggressive, infrequent sessions. It’s compound interest for your body. Small deposits, exponential returns over time, versus those sporadic large investments that never quite pan out.

When I finally made this shift (sometime around early 2023, I think?), the change wasn’t immediate. But after maybe six weeks, I noticed I wasn’t groaning when I stood up from my desk anymore. My hip flexors weren’t permanently cranky. I could put on socks without a whole production.

Small stuff. But also… not small at all.

Shift Three: Your Body Isn’t Made of Parts (It’s Made of Lines)

Third shift is conceptual—a mental reframe more than anything—but it’s honestly been the most revolutionary for me.

Stop thinking about individual tight muscles. Stop diagnosing yourself with “my hamstrings are tight” or “my lower back hurts” like these are isolated incidents. Because your body doesn’t organize itself into the discrete muscle groups we see in anatomy textbooks. It functions through integrated chains, fascial lines that run continuously through your entire structure.

Consider this: there’s a posterior chain (fascial line, really) that starts at the bottom of your foot—literally the plantar fascia—and runs up through your calves, into your hamstrings, across your sacrum, along all those back muscles, into your neck, and technically all the way up to your scalp. It’s one continuous line of connective tissue.

And here’s the thing—restriction anywhere along that line affects the entire system. Your “tight hamstrings”? Might actually be compensation for immobile ankles. Or a stiff mid-back. The hamstrings are just the loudest complainers, but they’re not necessarily the root problem.

The one-degree shift is mobilizing fascial lines instead of attacking individual muscles. This means flowing through connected sequences: a calf stretch that melts into a hamstring wave (think more undulation, less static hold) that extends into a hip hinge that spirals—and I mean actually spirals, rotation is hugely underrated—into thoracic spine movement.

These mobility flows are based on work by this anatomist Thomas Myers and his whole Anatomy Trains concept, which sounds very California wellness-y but is actually legit biomechanics. The body’s real functional architecture works in lines and spirals, not in the isolated movements we typically stretch.

The compounding impact? When fascial lines move freely, power doesn’t leak. Energy you generate at the pedals actually makes it to the pedals instead of dissipating through stuck segments in the chain. There was a study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research showing that improving hip mobility specifically—just hip mobility—enhanced cycling economy. Same power output, less oxygen needed, purely because the biomechanics got more efficient.

I mean, that’s essentially free speed. (Though nothing in cycling is really free, is it? There’s always a cost, usually measured in suffering or money or both.)

Over years of doing this—and I’m talking years, not weeks—you accumulate suppleness instead of rigidity. Resilience instead of fragility. You become the kind of cyclist who ages gracefully into the sport instead of aging out of it.

So Here’s Your Actual One-Degree Shift

The captain doesn’t need to crank the wheel dramatically. Barely touching it is enough—imperceptible in the moment, undeniable when you arrive.

Your one-degree shift in cycling flexibility isn’t about adding hours to your already-packed schedule or becoming a yoga master or buying some special equipment. It’s way simpler and maybe more difficult because of that simplicity: choose dynamic over static. Choose integrated over remedial. Choose systemic over isolated.

Here’s what I’m asking you to commit to: 30 days. Just 30. Five minutes each morning doing a simple mobility flow. Hip circles—big ones, not timid ones. Leg swings front-to-back and side-to-side. Thoracic rotations where you actually rotate. Ankle circles and mobilizations because your ankles are probably more restricted than you think.

That’s it. That’s the whole commitment.

And then pay attention (this part is crucial)—notice how your body feels on the bike. Notice whether that chronic tightness in your lower back whispers less insistently. Whether getting into your riding position feels more fluid than forced. Whether you can actually enjoy the last hour of a long ride instead of just surviving it.

One degree. Thirty days. The trajectory of your cycling life—and I’m not being hyperbolic here—begins its arc toward a completely different destination. One where performance and longevity aren’t opposing forces you have to choose between. Where you’re not just riding faster but moving better through the world. Where the bike remains a source of genuine joy instead of a catalog of compensations and complaints you’re managing.

The question was never whether a one-degree shift matters.

The question is: which port do you actually want to reach? Read More about Cycling Training Here.